Viet Nam Human Rights

»

Analysis-Comment

»

home

»

Are foreign criminals using human rights to avoid being deported?

Viet Nam Human Rights

»

Analysis-Comment

»

home

»

Are foreign criminals using human rights to avoid being deported?

Are foreign criminals using human rights to avoid being deported?

27/8/16

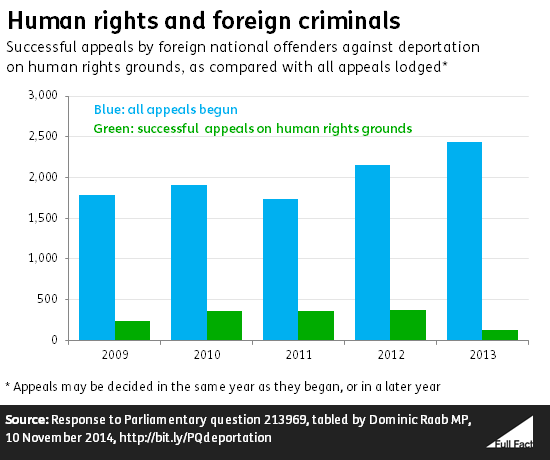

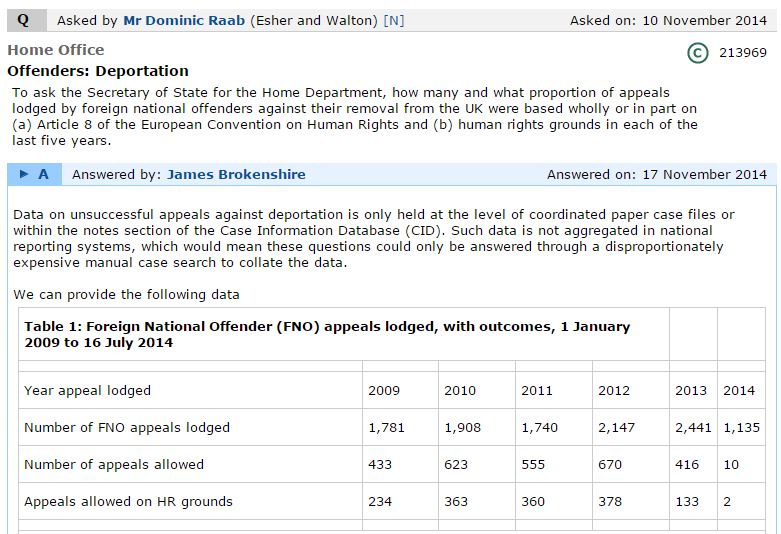

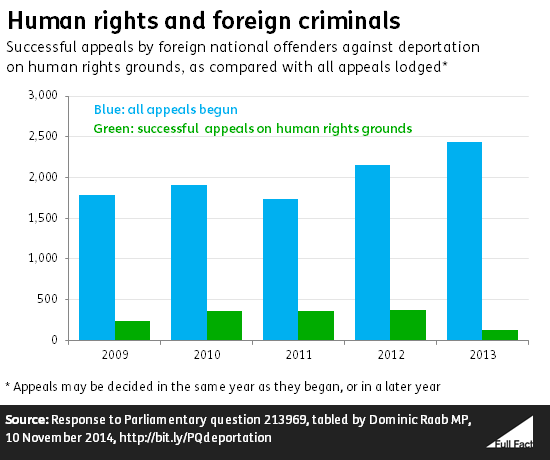

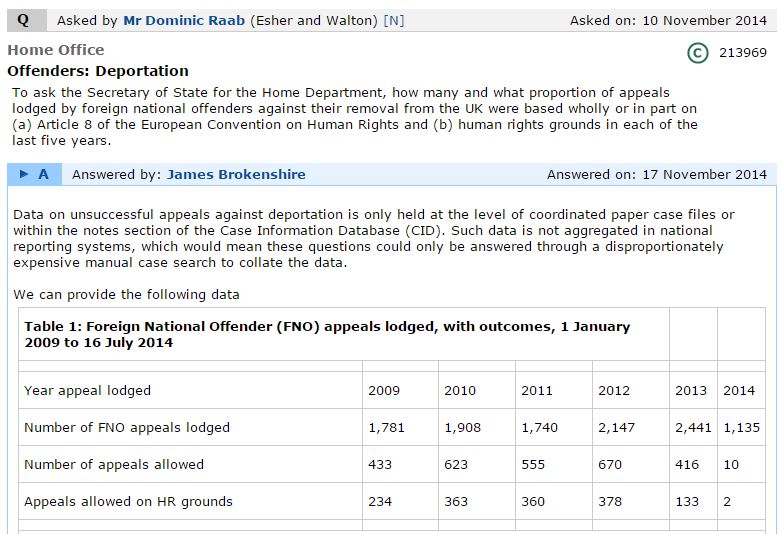

A couple of thousand foreign nationals convicted of criminal offences in the UK appeal against being deported every year, and every year a few hundred appeals are granted under human rights laws.

The Home Office says that 133 foreign criminals were allowed to stay in the country out of respect for their human rights in 2013. That's five per cent of all appeals by offenders from another country decided that year, but around a third of successful appeals.

But it stresses that the figures are provisional and haven't been quality assured. We should also be cautious about drawing conclusions from the numbers for 2014, as they only cover half the year.

The Human Rights Act 1998 allows judges to stop public authorities from acting in breach of the rights contained in it. This includes deporting someone if they would be at risk of "torture or inhuman or degrading treatment" in their home country, or to avoid breaching the right to "respect for private and family life" (which was singled out by the Prime Minister in Parliament last week).

Replacing the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights wouldn't stop criminals, or anyone else, going to the European Court of Human Rights with their case. Pulling out of that system is a separate decision, as is changing the law giving human rights exceptions to automatic deportation for foreign criminals.

It's certainly true that human rights law can be invoked by anyone to whom it applies, including those convicted of serious criminal offences. The courts can't turn people away on this basis.

Human rights and criminals in our courts

Most cases involving human rights will now take place in the UK courts. So far as we know, there's no way of telling what proportion of them involve criminals or suspected terrorists.

Looking only at cases where a court has declared legislation 'incompatible' with the ECHR—inviting Parliament to change the law, although it doesn't have to—convicted criminals or terrorist suspects have accounted for 12 of the 28 decisions so far.

Foreign criminals avoiding deportation

A couple of thousand foreign nationals convicted of criminal offences in the UK appeal against being deported every year, and every year a few hundred appeals are granted under human rights laws.

The Home Office says that 133 foreign criminals were allowed to stay in the country out of respect for their human rights in 2013. That's five per cent of all appeals by offenders from another country decided that year, but around a third of successful appeals.

But it stresses that the figures are provisional and haven't been quality assured. We should also be cautious about drawing conclusions from the numbers for 2014, as they only cover half the year.

These human rights claims might be on the basis that the person in question would be at risk of "torture or inhuman or degrading treatment" in their home country, or to avoid breaching the right to "respect for private and family life".

European cases and criminals

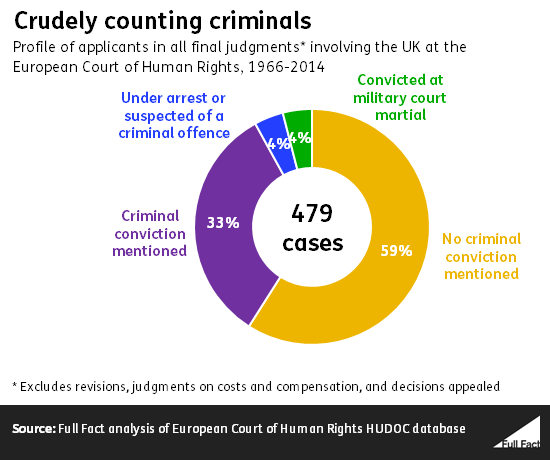

We can also look at judgments involving the UK at the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

In a significant minority, at least one person involved had been convicted of a criminal offence at one time or another (some at a military court martial). But around three-fifths had no connection to a criminal case at all.

This doesn't necessarily reflect the overall picture, though: thousands of applications to the Court never make it as far as a judgment, and some judgments can resolve many individual cases.

Criminal justice rights

It's not particularly surprising that there are European human rights cases involving people convicted of a criminal offence. Some ECHR rights are designed with them in mind.

For example, Article 6 of the ECHR protects the right to a fair trial. It sets out "minimum rights" that someone charged of a criminal offence is entitled to before and during their trial.

You would expect to find people convicted of a crime, in circumstances they consider unfair, to rely on this article before the Court. For instance, Cuscani v United Kingdom concerned an Italian man who had been convicted of tax offences here. He didn't speak English very well, and the Court decided that his conviction had been in breach of Article 6 because no interpreter had been provided.

Mr. Cuscani is a criminal for the purposes of our first graph. We've also factored in people convicted of offences in another country—which includes Abu Qatada, who was never convicted of a crime in the UK, but had been in Jordan.

Many of the cases in which we've recorded one or more of the applicants as "under arrest or suspected of a criminal offence" concerned Northern Ireland. A series of judgments have been given about people arrested, or shot and killed, when it was suspected that they were IRA members. The case doesn't always record whether or not this was true, or whether the person involved had any convictions for terrorist offences.

Human rights are designed for minorities

Giving legal protection to people who aren't necessarily popular in wider society is what human rights are all about. Gay people wishing to serve openly in the military or gypsies resisting eviction from public land may not be able to get public support for their interests through the democratic process. This may change over time—attitudes to gay people, for example, are very different in 2015 than over most of the last century.

Criminals and prisoners, by contrast, are perennially unpopular. Supporters of human rights law would say that this is all the more reason to protect their human rights. Others argue that certain categories of behaviour should lead to at least some of these protections being forfeited—a concept reflected in the Conservative proposals for a replacement to the Human Rights Act./.

Popular Posts

-

Religion is a part of the spiritual life in society, this phenomenon of the superstructure has been strongly changed with economic - social...

-

Vietnam has just done well for the second cycle of Universal Periodical Review (UPR) in Geneva, Switzerland. So, what’s the UPR? an...

-

Representatives from foreign countries congratulate Viet Nam on its election to the Human Rights Council for the first time on November ...

-

A street flowers vendor in Hanoi Another new spring has come to Vietnam, bring...

-

Thai people in Shutdown Bangkok protests Not until this crisis, we have realized the ne...

-

If nothing changes, there will be a preferential credit program with hundreds of thousands billion of capital for agriculture and r...

-

Recently, several anti-governmental individuals have established series of illegal groups and organizations in the name of civil soci...

-

Child sexual abuse has been on the increase in Vietnam in recent years according to the Ministry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs....

Blog Archive

-

▼

2016

(

423

)

-

▼

tháng 8

(

34

)

- Around the right to an adequate environment

- GMS officials discuss ways to improve food safety

- Reactionary portraits: Brotherhood for Democracy ...

- Vietnam condemns violence against children before ...

- Lien Tri Pagoda incident: Land clearance for natio...

- Vietnam's economy: The next Asian tiger

- Policy targets fishermen in four central provinces

- Value of Ho Chi Minh's thought “Nothing is more pr...

- Vietnam urged to become a more competitive market

- HAS CHINA SHOT ITSELF IN THE FOOT BY REFUSING THE ...

- Fighting corruption is a supplement to the enjoyme...

- Impacts of free trade agreements on Viet Nam’s eco...

- China’s cyber attacks threaten Internet freedom

- Impacts of free trade agreements on Viet Nam’s eco...

- Reverie of Vietnam

- Impacts of free trade agreements on Viet Nam’s eco...

- Vietnam Buddhist Sangha congratulated on Vu Lan fe...

- Vietnam’s religious freedom in real life

- Will of the nation makes invincible power

- Government religious committee meets Muslim dignit...

- Religious freedom in Vietnam is an undeniable

- Charlie Hebdo: the French Free Speech?

- Vietnam has many important contributions to the de...

- Poor lives of children in Syria war

- More localities pledge to create favourable busine...

- Are foreign criminals using human rights to avoid ...

- History cannot and should not be distorted

- Deputy PM urges quicker institution building for r...

- Embassies show strong performance in protecting Vi...

- Ministry proposes options for resuming fishing act...

- Refugee and migrant children are becoming stranded...

- Information-communication sector sees leaping growth

- Women's Rights Are Human Rights

- Vietnam’s various ethnicity in national solidarity

-

▼

tháng 8

(

34

)

All comments [ 0 ]

Your comments